What happened at the Potsdam Conference, and how does it continue to shape the world in which we live?

Watch a live panel discussion, moderated by Stanford professor Norman Naimark, featuring George P. Shultz, Stuart Canin, and Stanford professor Scott Sagan, that sheds light on what happened at Potsdam when Canin was there.

Read the introductory text below adapted from remarks given by Norman Naimark on November 19, 2014, at Stanford’s Bing Hall. Professor Naimark is the Sakurako and William Fisher Family Director of the Stanford Global Studies Division, the Robert and Florence McDonnell Professor of East European Studies, and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

Potsdam was the third and final Big Three conference that set the terms for the end of the Second World War.

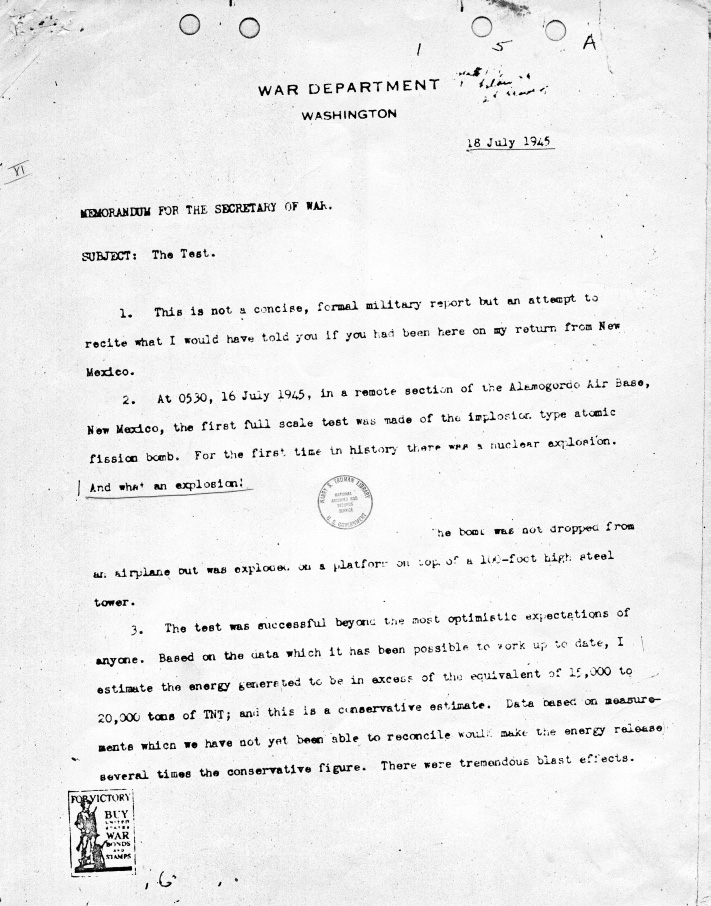

The Allied leaders—representatives of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, the so-called Grand Alliance—met in Tehran in November 1943, Yalta in February 1945, and then Potsdam from July 17 to August 2, 1945. In the months separating Yalta and Potsdam, several key changes took place. President Roosevelt died in April, leaving Vice President Harry Truman to assume the presidency and take up the final negotiations. Prime Minister Clement Attlee defeated Winston Churchill in the British general election and replaced him as Britain’s representative halfway through the Potsdam Conference. Joseph Stalin attended all three major conferences; by the time the Potsdam Conference began in July, he effectively controlled all of Eastern Europe.

Despite differing politics, the Allies shared common goals at each conference: first and foremost, to end the war in victory. After all, this had been the bloodiest war in the history of the modern world; all were eager to bring it to an end by any means necessary. The secondary goal was to secure the peace.

The Allies achieved their primary goal of victory, but securing the peace proved difficult. The events of the war and of these conferences led almost inexorably to the Cold War, from one set of dangers to another.

The Big Three triple handshake, Charles Hodges Photographs, Envelope K, Hoover Institution Archives, courtesy of Hoover Institution Library & Archives, Stanford University

The Big Three and their foreign ministers, Charles Hodges Photographs, Envelope K, Hoover Institution Archives, courtesy of Hoover Institution Library & Archives, Stanford University

The next negotiations at Potsdam established the Allied Control Council, which determined how Germany would be divided and ruled.

Stalin was interested in this issue because his troops were in Central and Eastern Europe, and he wanted to secure the entire region as a sphere of influence for the Soviet Union. The Allied Control Council would occupy four zones in Germany, and four zones in Berlin. The Allies agreed to focus on the three ds: deNazification, demilitarization, and democratization.

But the Allies could not agree on the issue of reparations. Stalin came to Potsdam for money to rebuild his destroyed country. He wanted the reparations from Germany that Roosevelt had promised at Yalta. Truman, on the other hand, felt Germany needed to be rebuilt, to become an export country once again so that it could support itself. He didn’t want the American taxpayers to have to pay for food and sustenance for the German people. So Truman and his secretary of state told Stalin that if he wanted reparations, he could take them from his own zone.

That’s exactly what the Soviets did. They took nearly ten billion dollars’ worth of reparations from the Eastern zone, tying Eastern Germany to the Soviet Union for the next several decades. Many historians believe that this reparations deal was crucial in dividing Germany.

Destruction on a city block in Nuremburg, 1945, Stuart Canin Papers, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University

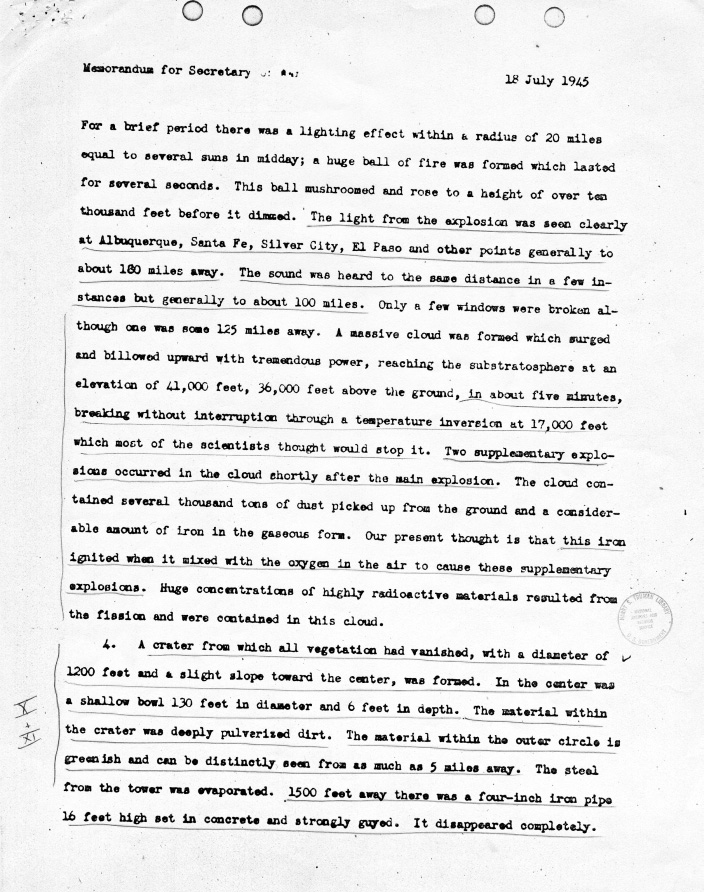

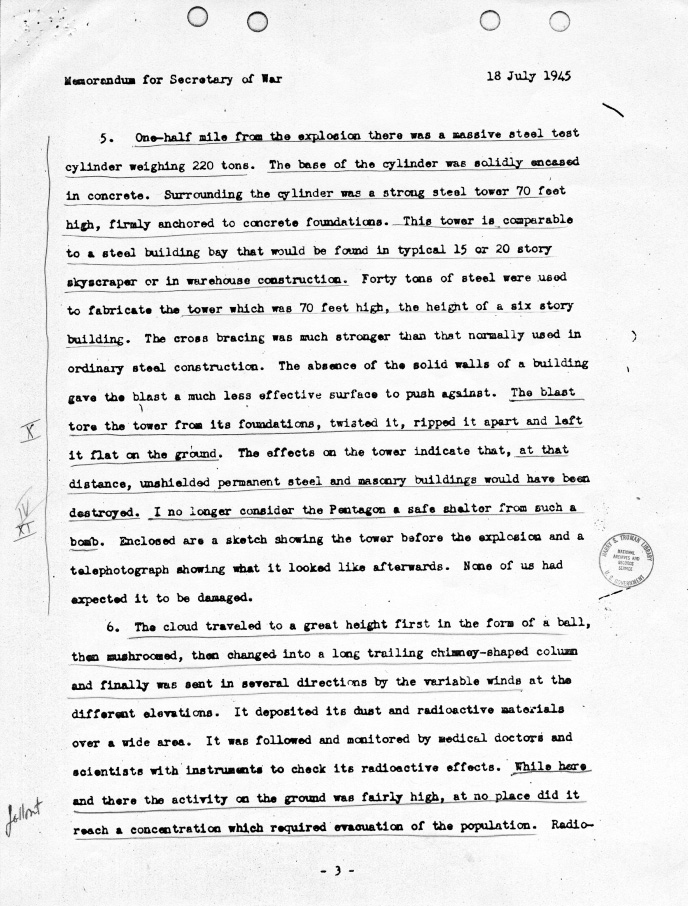

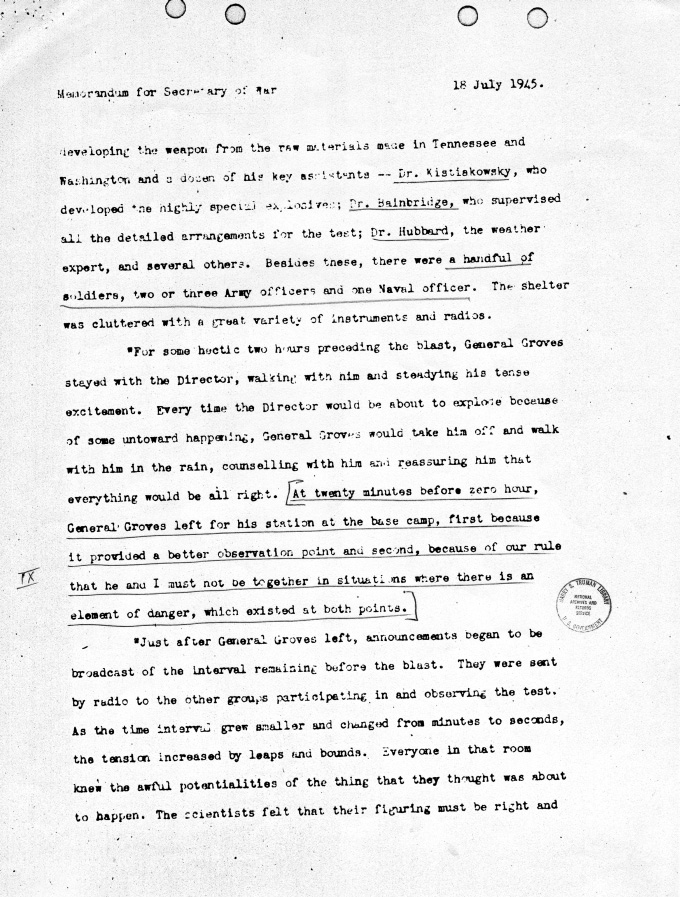

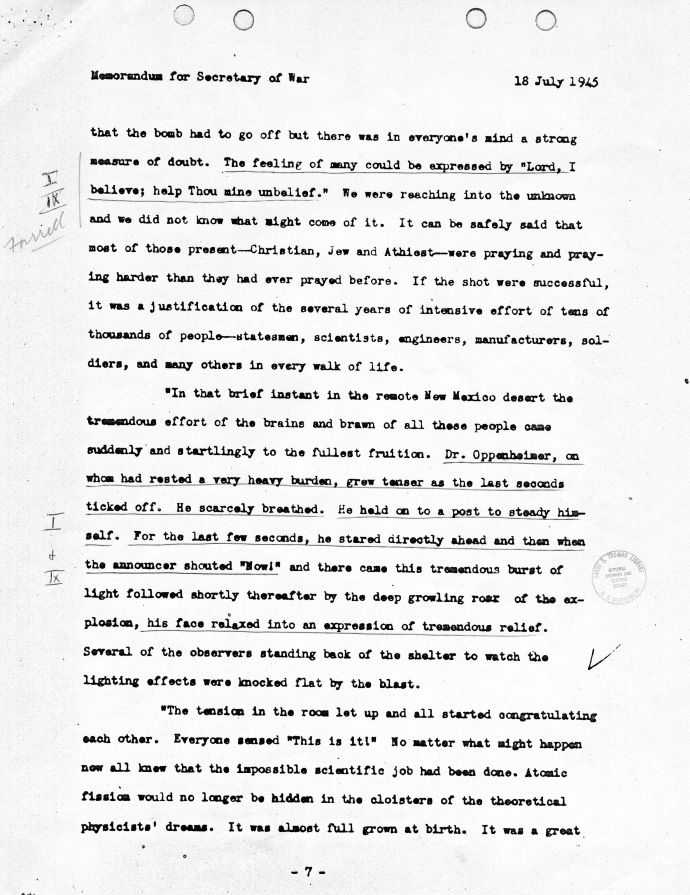

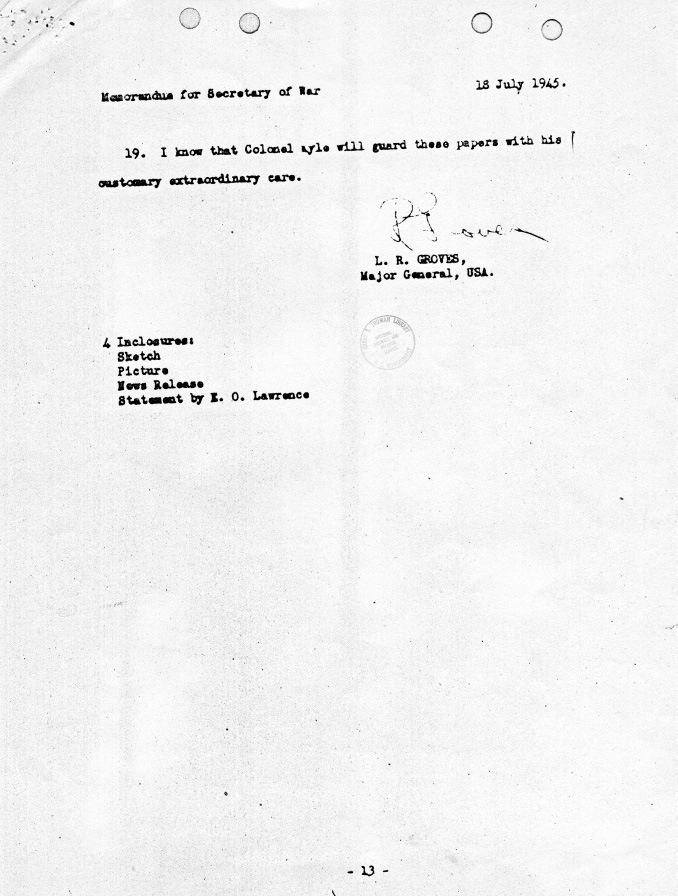

The final issue that came up at Potsdam was completely unprecedented. On July 16, Truman learned of the successful detonation of the atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert.

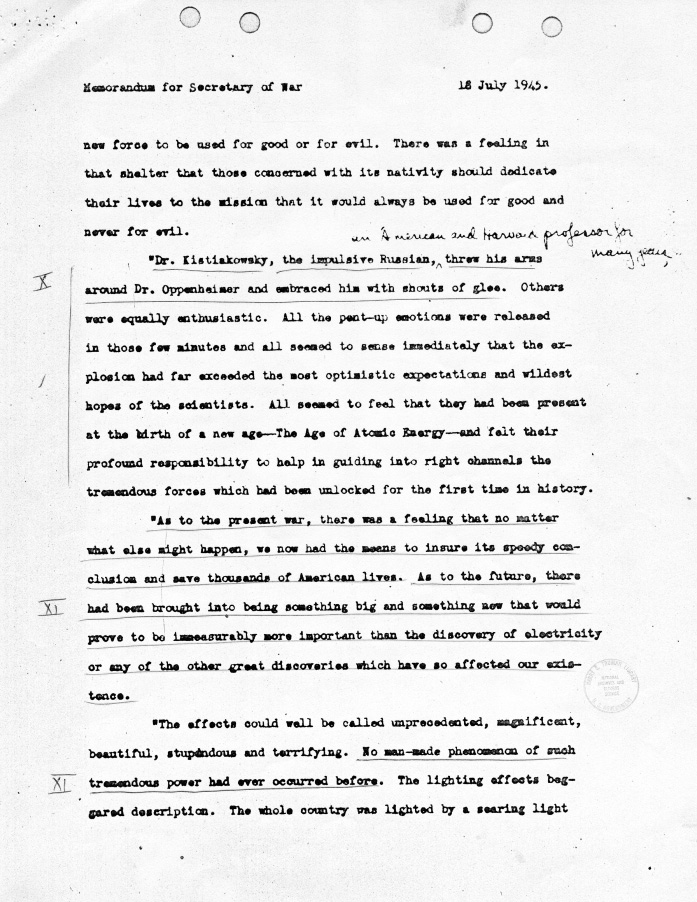

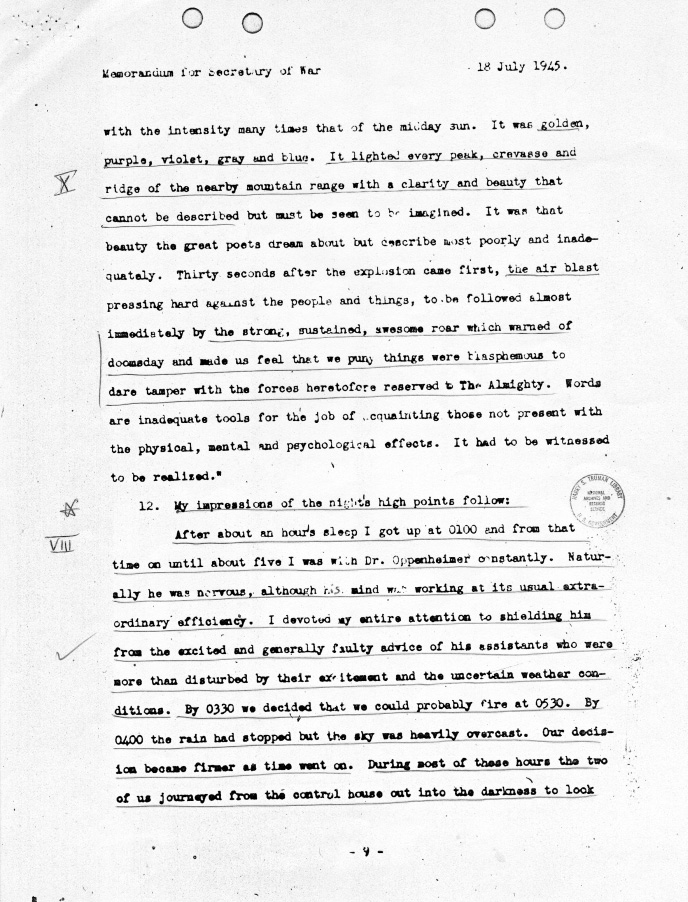

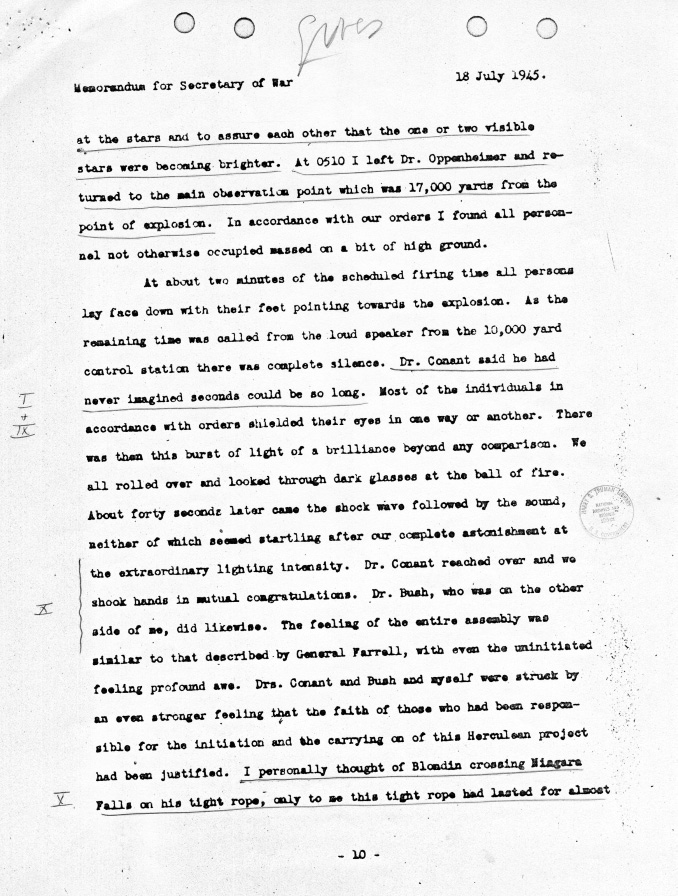

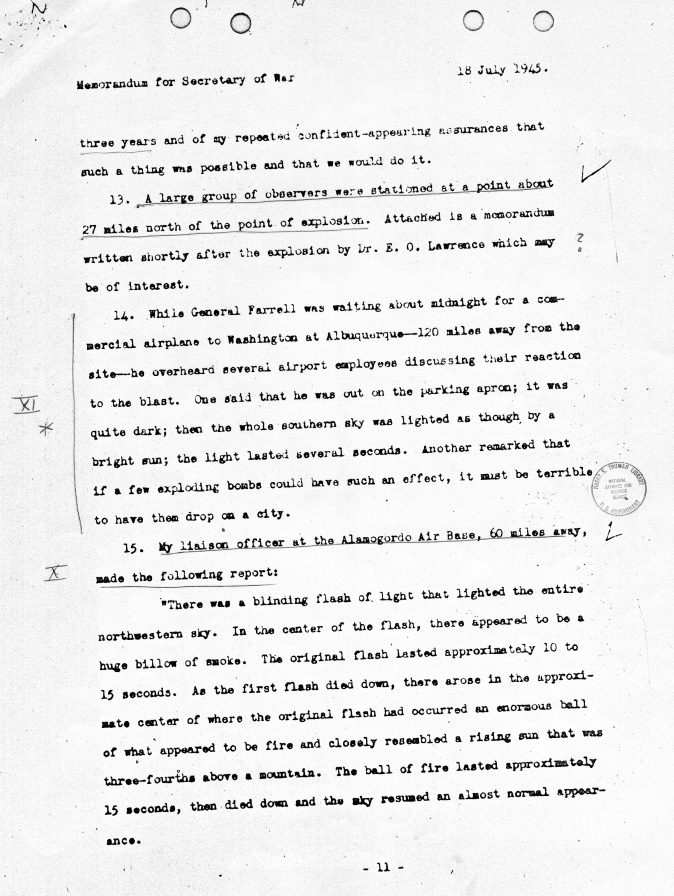

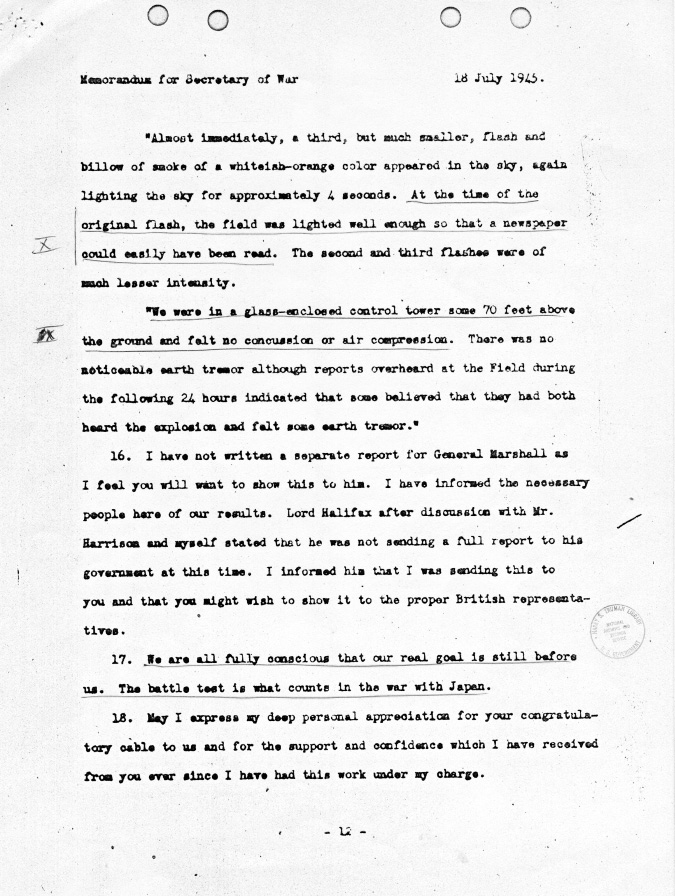

Then on July 21, he received a long memorandum from Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, who oversaw the Manhattan Project, describing in detail what he and the Manhattan Project’s scientific team had witnessed during the Trinity test: the sheer immensity of the destructiveness of that bomb.

This knowledge buoyed up Truman. Witnesses all say the same thing: that Truman now seemed a little lighter on his feet when negotiating with Stalin. Before this news, Stalin was sitting on top of the world. But with the atomic bomb, the Western Allies felt they now had a bargaining chip.

Leslie. R. Groves to Henry Stimson, July 18, 1945, imaged and archived by the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

On July 24, Truman sauntered up to Stalin and whispered in his ear, “We have a bomb of enormous destruction.”

He did not say it was an atomic bomb, and neither did he threaten Stalin directly. Its existence alone posed a threat to Soviet power. Everybody was watching Stalin’s reaction, but Stalin remained completely placid, playing it straight.

This reaction to the bomb, and then the use of the bomb, began an era in which the bomb was inextricably tied to East-West relations. These origins of the Cold War and of atomic diplomacy make Potsdam resonate with us all today, seventy years later.

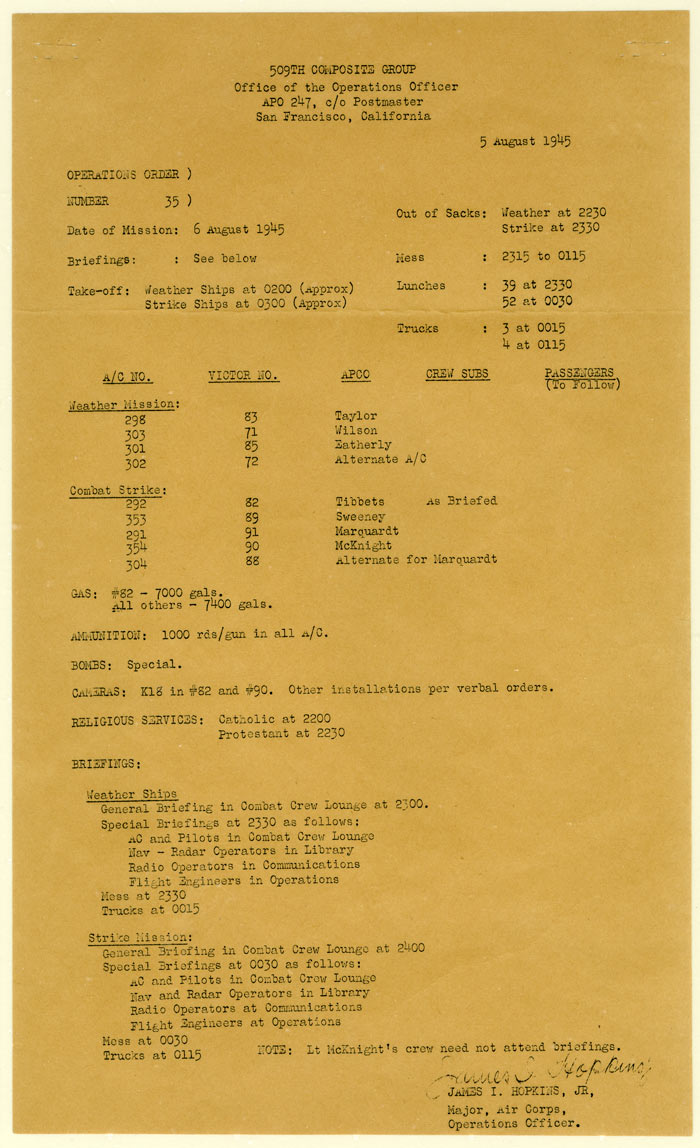

Strike order of Hiroshima mission, Strike Order #35, United States, Army Air Forces, 509th Composite Group operations orders, Hoover Institution Library & Archives, Stanford University

“Potsdam Big Three Meeting!” newsreel by Paramount News & Signal Corps Films, July 1945, archived by the US National Archives and Records Administration